The wunderkind steps out.

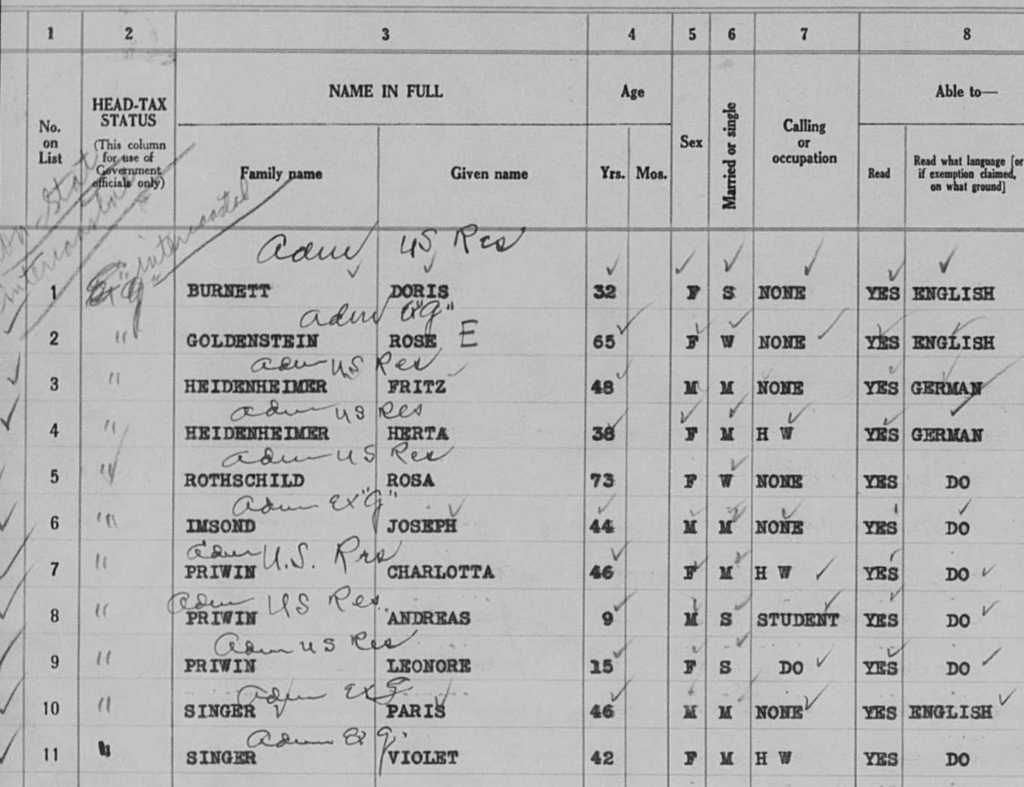

Andreas Ludwig Priwin was a prodigy. He was born in Berlin in 1929 (or perhaps, as he himself thought, 1930—his birth certificate was lost in the war). He enrolled in the Berlin Conservatory at the age of six, having earned a full scholarship. In 1938, he was expelled for being Jewish. He and his family made their way to Paris, with only enough money and possessions to maintain the illusion of a weekend getaway. They waited for nine months to get visas to enter the United States; in the meantime, Andreas learned French, took theory classes at the Paris Conservatoire, and had some lessons with another prodigy, Marcel Dupré. Finally, toward the end of 1938, the family sailed to New York City, and then to Los Angeles, where Andreas changed his name to André Previn and embarked—in remarkably short order—on one of the more polyvalent musical careers of the last hundred years.

Previn, by his own admission, didn’t care much for jazz at first, until he saw the light, in the form of Art Tatum’s recording of “Sweet Lorraine.” Previn recalled his father giving him the record and, in an assignment of equal parts industry and ego-tempering, telling him to “learn it,” which Previn did. (It took him, he claimed, three years.) That got Previn up to speed on jazz style, but not the practice of improvisation. But prodigies are, by definition, quick studies.

The earliest André Previn performance I’ve been able to find dates from December 1944, when Previn was still 15 (or, perhaps, 14), but nonetheless already had been working in radio for a couple years. He appeared on a short-lived program called Music Depreciation, in which swing and jazz numbers by regulars Frank DeVol and Les Paul and weekly guests were interspersed with Ruben Gaines’ comic parodies of the sort of florid, programmatic descriptions of classical music epitomized by Walter Damrosch’s Music Appreciation Hour. Previn plays a fluent but repetitive slow-then-fast reading of Gershwin’s “The Man I Love.”

Previn returned to the show the following February in better form; his version of “My Blue Heaven,” which makes room for brief quotes of both Gershwin and Ellington, has charm to spare.

Later in 1945, Previn was a guest on Jubilee, an Armed Forces Radio Service program that most often featured African-American performers and was intended for African-American overseas troops. Previn’s performance of “I Surrender, Dear” is very much in the vein of Nat “King” Cole, but Previn set himself a high bar by collaborating with bassist Red Callender and guitarist Irving Ashby, once and future members of Cole’s trio.

Previn still sounds a little raw, if you listen close: his left-hand comping is serviceable but repetitive, and his right-hand riffs—glittering as they are—don’t really gather into larger structures. (The descending pentatonic flourish that turns up in both of these performances will lurk around Previn’s playing for a while.) But this is nitpicking. The ease, flair, and confidence are already there.

Many of the riffs Previn deployed on that Jubilee spot turned up again later that year in sessions at Hollywood’s Radio Recorders studio. They were recorded for Sunset, an independent label run by Eddie Laguna, who had been occasionally hiring Previn for concerts, including one at the Philharmonic Auditorium in Los Angeles. (Laguna was an obscure and private figure, to the point that, for a time, some people thought the name was a pseudonym of Nat Cole, who also recorded for Sunset.) Previn was still favoring a Cole-style trio, this time with guitarist Dave Barbour and bassist John Simmons, experienced sidemen who had briefly played together in Benny Goodman’s orchestra. They don’t quite mesh; Simmons and, especially, Barbour, seem to be more on top of the beat than Previn likes, and he sometimes rushes to the next beat in response. The session is notable, though, for a pair of Previn originals. “Mulholland Drive,” a brisk roller-coaster over rhythm changes, is particularly charming.

Previn went back to Radio Recorders a few more times over 1945 and 1946, making a series of recordings that almost feel like a résumé. There’s a handful of small-group arrangements (featuring, among others, Willie Smith and Vido Musso on sax and Previn’s fellow prodigy Buddy Childers on trumpet). There’s another trio date, a reunion with Ashby and Callender yielding largely straightforward versions of Ellington staples, the best being a spare and spacious take on “I’ve Got It Bad and That Ain’t Good.” (In 1952, Monarch would release these tracks as André Previn Plays Duke Ellington.)And there’s some solo piano, including a driving, up-tempo “Body and Soul” that runs out of ideas before it runs out of steam, and an original “Variations on a Theme” that swings between straight-ahead jazz embroidery and French Impressionism, never quite bringing the two together but fully comfortable in each. Most of these were released on the short-lived Sunset Recordings label, and several re-released on the Monarch label in the 1950s. (A couple of the small-group takes were issued as “The Willie Smith Six”—technically, Previn’s first credits as a sideman.) But, taken as a whole, they feel a bit like a course of self-directed study, Previn honing his arranging skills, his adaptability, and his assurance in a studio setting before making a splash. (Most of these early recordings have been assembled and reissued as Previn at Sunset (Black Lion, 2002).)

Of course, Previn had already been accepted into a graduate school, of a sort. In 1945, while still a student at Beverly Hills High School, he was hired onto the musical staff at MGM Studios. His first job, he recalled, was a jazz number: writing out some boogie-woogie for pianist José Iturbi to play in 1946’s Holiday in Mexico. Once the film came out, Previn had the opportunity to joke about the sequence with Frank Sinatra on Songs by Sinatra, the singer’s weekly radio program.

Previn became something of a regular on Sinatra’s program throughout the autumn and winter of 1946, the emphasis invariably on Previn’s youth, studio bona fides, and piano skills—“the big hands of the big little boy with the bigger talent,” as Sinatra first introduced him. (Previn got to turn the youth angle around on the 30-year-old Sinatra in a recurring feature in which Previn accompanied groups of old Tin Pan Alley favorites, Sinatra showing “Junior” what it was like “in the good old days,” as Previn joked, when you were young.”) Previn’s Songs by Sinatra appearances foreshadowed much of his future career—and not just jazz, or even easy-listening (as when Previn would add his piano to Axel Stordahl’s sumptuous orchestra): on the October 16, 1946 show, Previn played an abridged version of the first movement of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto no. 2.

To hear just how fast Previn was going at the time, compare his second appearance on Jubilee, from 1946, with four sides recorded live at a 1947 “Just Jazz” concert produced by Gene Norman and released on the Modern label. In a reading of “Lady, Be Good!” at the earlier performance, Previn tentatively tries out some whole-tone-scale decorations and, comping under guitarist Barney Kessel’s solo, a couple of discreet call-and-response echoes, but mostly stays recognizably within his initial, Cole-meets-Tatum style (as does another performance of the song on another AFRS program, Command Performance, in December of 1946). In 1947, with (most likely) Ashby, Callender, and drummer Jackie Mills, Previn’s take on “Lady, Be Good!” is essentially similar and yet completely different, having gone from confident to cocky in the best way. The whole-tone patterns are thrown down like challenges, and Previn shadows Ashby’s solo in downright mischievous fashion. You can almost see the grin on his face. He’s ready.